Tokyo Masked

“In a Station of the Metro” by Ezra Pound

The apparition of these faces in the crowd:

Petals on a wet, black bough.

As some sense of normalcy returns to Tokyo, I’ve restarted in-person classes, in-person commutes, and a few meals out. But Tokyo is not the same. It might not ever be the same. It’s become a faceless city. I’m not against masks, or against hidden things in general, but I do miss seeing everyone.

Everything that made Tokyo a fascinating place—intimate restaurants, teensy stores, standing bars, underground (and unaired) clubs, and the constantly close life—makes Tokyo a great place for virus exchange. If I were a virus, I’d choose Tokyo, once the city with the greatest aerosol exchange of any place on earth. In containing the viral aerosol, we’ve given up faces.

As a novelist, I’m an observer of people and have never minded my commutes for just that reason. Public space was a place to learn. Watching an overworked salaryman dozing, the determined glare of a student pouring over a study book, the day-off indifference of a young couple shopping, were more than observations. They were stories. With everyone masked, I feel cut off not just from other people, but from their stories, too.

Stories come through the body, too, I suppose, but less so. Japanese always have a body politeness in public that is rare in most other cultures. And that’s been doubled with everyone masked. It’s making everyone tenser than they used to be, more aware of mawari no hitotachi, “the people around.” They are more restrained, and more aware, but mostly they are more hidden.

It used to be that some women on the train, and men, too, would spend a chunk of their commute grooming themselves, putting on make-up, adjusting their hair, checking their bangs. They’d use hand mirrors or cellphone cameras for self-scrutiny or stop by a window or shiny metal surface to give themselves a check. But no longer. They can’t see through their own masks. Once they’re roped over the ears, there’s little left to primp.

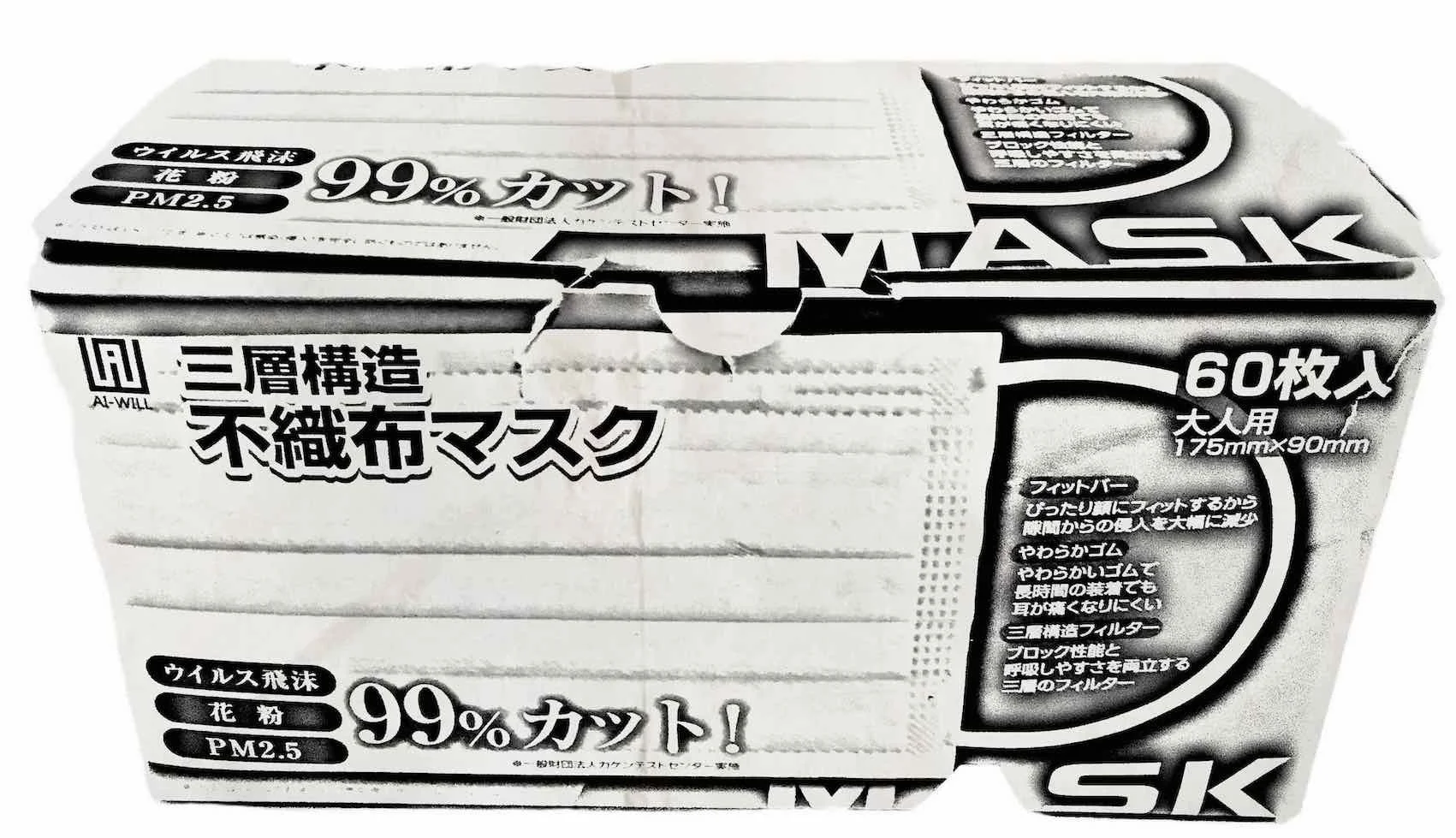

With masks, I’d hoped that Tokyo would do its usual thing and start juicing up the design. But that hasn’t happened. I’ll see a few cool ones, a photo-shopped same face, zingy ethnic colors, a dark indigo swath that matches an outfit, but generally, it’s plain hospital white, punctuated by grey or black. On the train, the masks form a giant ellipsis down the row—white white white, dot dot dot.

Or maybe not entirely. There are the eyes. I look into them more than I ever did before. Japanese have always been great at the side-glance, the peripheral taking-in of everything around them. It’s an urban necessity. But now, it’s as if the energy of the face has been compressed into the eyes. Floating over the white below, they seem more sensitive, more alive. But even with the help of eyelids, eyebrows, foreheads and the brush of a cheek, the eyes can’t do all the work a full face can.

Tokyo’s always been a city of secreted spaces, dark interiors, and the unseen insides of offices and private homes. Frankly, few people could claim to have seen much of the inside of Tokyo at all. You can see the few spaces you have access to, but not much else. In Tokyo, you’re only ever invited into a small fraction of interiors. But now, there are front doors on all the faces, too.

It breaks my heart that one of the greatest joys of the city—the endless flow of faces—has become blockaded. The city’s become a walking cloister, not a blindfold but a face-fold. It’s like a Shinto Shrine, where the innermost space remains covered by a wide sudare bamboo screen, the gods there but unseen. The people are there, but imagined rather than sensed. The fewer peeks into the passing lives turn the city toward harder mysteries.

I notice this feeling in my classroom, where we all stay masked. Over the years, I’d learned to read students’ faces for unspoken questions and hints of confusion, and for just the opposite, the satisfaction of realization and the welcome surprise of understanding. Now, where I used to read response, I get blank pages. I’m forced to ask students more what they think, which isn’t bad, but it’s slower than a quick read of their faces.

Outside my classroom, all through the city, Tokyo’s become like that for me, too, slower to read. Without faces, the city feels farther away, even when I’m in the middle of it. As a writer, observing people’s faces and imagining their stories used to be the workout of my day. Its absence leaves an aching sense of loss.

When all the stories pass by masked, I feel cut off from the interplay with the unknown, the posing of questions, the spur to imagination that used to mark my people watching. Without the daily flow of faces, Tokyo’s a different city altogether, safer, yes, but less itself.

Hidden faces on unfilled trains

White petals hiding worlds inside.

Michael Pronko

December 2021