Missing Meishi

During the pandemic, the diameters of my social circles haven’t budged. I’ve met no one new. I know that because I don’t have any new meishi name cards. I haven’t given or received one for a year and a half. The drought of new meishi makes me miss meeting new people, especially since there are so many in Tokyo.

Before the pandemic, a new meishi was clear evidence of entering into a new circle of exchange. I loved that ritual of moving from outside to inside, from not-knowing to knowing, from separate to connected. It’s a way of leaping over differences and distances, to enter another ring. In Tokyo, it’s not what you know, it’s whose meishi you have.

To be honest, I’m not that much of a schmoozer. I exchange meishi at jazz clubs, at academic conferences, and with the occasional TV program or publisher, but I’m not a salesman, who thrive on meishi. In fact, I could live just fine without ever exchanging another one.

But I enjoy the ritual. There’s something intriguing about carrying someone’s contact data home in your pocket, even if you never use it.

Meishi is a very old ritual, a remnant of when it was impossible to reconnect unless you had some sort of paper record of contact, back when phones were fixed to a wire and maps were on paper. Like a lot of rituals in Japan, it has staying power. And like a lot of seemingly small things in Japan, it took me a while to master the polite phrases, the correct manner of giving and receiving a card, the subtleties of lingering over a card and making some small, nice comment. It’s not just a card, it’s an intricate series of gestures.

I’ve learned to leave the card in front of me on the table (careful to avoid the wet spot from my drink). Having it there is a helpful reminder about the new person’s name, affiliation and position, which are easy to stumble over. I’ve also learned when and how to place the new meishi in my name card holder. Jamming it into a crammed-full wallet would ruin the new relation by disrespecting the integrity of the card and all it represents.

Japanese judge Japanese-ness by these small, subtle details, and seem to reset expectations based on performance. In a sense, it’s no different from a hearty handclasp, the western handshake, which can tell a lot about the person. But meishi are a handshake you can take home with you.

All employers print meishi for their employees, but I never take the ones from my university. I miss out on the official university logo and font, but I like to get mine special-made on Japanese paper. It’s nicer looking and feels better in your hand. There are meishi printing shops all over the city, and I’ve been going to the same one for years. They keep my data on file. I buy them in batches of 300 or so.

Deciding on the meishi printing is a project in itself. The shopkeeper pulls out books with samples of paper, one-sided or two-sided, colored, thick, thin, western, Japanese. We go over the font for English and for Japanese, the positioning of the letters and discuss the ink. It takes a week or so to print them, after which I pick them up in person and check them carefully. You can do all that cheaper and quicker online these days, but the old-style shop feels like part of the larger ritual.

I keep my meishi in five different places: my university office, my day-to-day bag, the camera case I take to jazz clubs, my home office, and my wallet. I have a special soft-leather case. Or cases, I should say, since I have three. The office meishi I keep in hard plastic boxes from the printer, as no one would ever see those, and I always tuck a couple inside my wallet for unexpected situations.

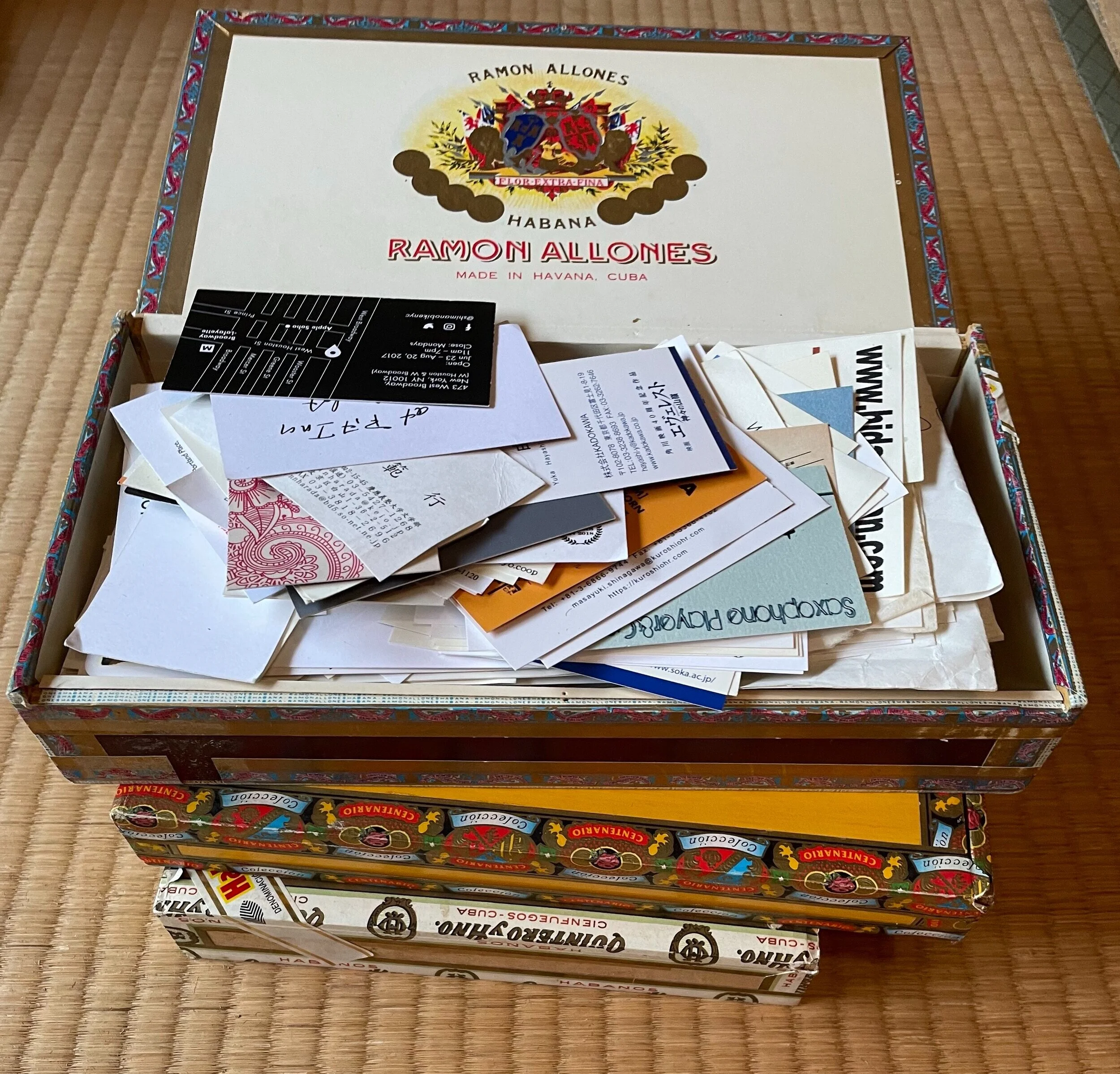

The meishi I receive I keep in cigar boxes, I hate to confess. I have different ones for academic, jazz, friends, and shops or services. Every so often, I organize them. Or I used to. Once, I bought a special meishi scanner, and a computer program to keep track of them, but email and the internet have swept even that. But technology will never be as beautiful, human, or succinct and simple, so I still love the feel of the paper in my hand.

I like to jot down notes on the back to remind myself of the details about that person. If I haven’t gotten back in touch or saved their info in my computer address book, I can forget who it was after a while. I like to be able to say, “I’m glad I ran into you” or “How’s your new job?” or “Let’s meet again.” It’s a mnemonic of that moment of initial contact. It’s a return ticket to that person’s world.

I even have meishi from shop clerks at department stores, the electrical appliance store, clothes repair people, anyone in a position where they provide a service, or have information I might later need. Shops and restaurants have them, too, though fewer now with QR codes, links, apps and other digital shorthand. I still pick them up. Artifacts from the in-person world, meishi seem to cast a stronger spell on me.

Even more than that, I feel the handing-over ritual serves as a magical transformation from being just one more person in a vast city overflowing with people, to a person with an address, a job, and a place in the world. It locates me in the dense nexus of the complex culture of Tokyo, where it’s easy to get lost. I meishi, therefore I am.

If I meet any of my former students after graduation, they always love to hand me their meishi. They pass it over with a gleam in their eye, marking their transition from student to shakaijin, a regular member of society. They bow and smile as they pass over that card, completing their student life even more than receiving a diploma.

Somehow, meishi always look to the future, holding a promise to return, to reconnect, to engage again. In that sense, meishi seem to be a kind of talisman for relations, a two-dimensional expression of potential. Maybe not quite a marriage certificate, or an official jirei job appointment, they are a miniature record of connection. Meeting people can be an achievement in Tokyo and deserves some written notice.

I’m always intrigued that not only do I have a lot in my collection, but mine are with other people. For all those I received, I’ve given an equal number given away, now in the filing system of people all over the city. I wonder about the meishi I’ve handed out, where they’ve traveled, where they’re filed. Do they ever think of me? Maybe not. Maybe they threw mine out, but I guess most people hang on to them like I do.

Mostly, of course, the meishi just sit on my shelves in my cigar box filing system. I’m sure Marie Kondo would advise me to throw them all out, but frankly, the meishi spark joy for me. I love the idea of having met those people, of having a record of interaction, of connection. It chips away at the anonymity of the city and connects the dots—of people and places and their people and places—you didn’t even know were there.

One of the ironies of Tokyo is that it’s so full of people, you can go for weeks—or a year and a half—and not meet anyone new. You’re surrounded by people and yet you don’t really know them at all. Meishi, though, are a kind of knowing, a feeling of not being isolated. That’s an illusion in some ways, just tatemae (superficial politeness), I suppose. But during the pandemic, I’ve missed that illusion just the same.

And when the pandemic eases, I wonder if the meishi exchange ritual will return, or will it all become an app, like everything else, or just be forgotten like a lot of parts of our pre-Covid lives. I hope they’ll still be used. I still have a couple small boxes left, ready and waiting, to be exchanged once again.

Michael Pronko

October 2021